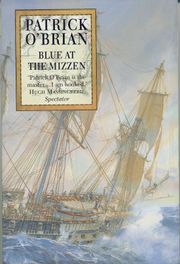

Blue at the Mizzen

From WikiPOBia

Oliver Mundy (Talk | contribs) (Themes and motifs) |

Oliver Mundy (Talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

By way of contrast, chapter 5 also gives us the last of O’Brian’s grand descriptive set-pieces in his account of Christine’s environment on the outskirts of Freetown. Like the Buddhist temple in ''[[The Thirteen-Gun Salute]]'', it is an idealised scene, an earthly paradise, rather than a wholly realistic portrayal – Sierra Leone was reckoned as one of the unhealthiest places in all Africa, and indeed Stephen nearly takes his death there in ''[[The Commodore]]'' – but one which is given verisimilitude by a number of precise details of fauna and flora, from the giant heron (''Ardea goliath'' actually exists: see [http://www.kenyabirds.org.uk/goliath.htm] ) and the nightjar ''Caprimulgus longipennis'' whose extravagant mating plumage seems to be an ironic comment on the ungainly wooing of Stephen which immediately follows, down to the leeches and mud-skippers. | By way of contrast, chapter 5 also gives us the last of O’Brian’s grand descriptive set-pieces in his account of Christine’s environment on the outskirts of Freetown. Like the Buddhist temple in ''[[The Thirteen-Gun Salute]]'', it is an idealised scene, an earthly paradise, rather than a wholly realistic portrayal – Sierra Leone was reckoned as one of the unhealthiest places in all Africa, and indeed Stephen nearly takes his death there in ''[[The Commodore]]'' – but one which is given verisimilitude by a number of precise details of fauna and flora, from the giant heron (''Ardea goliath'' actually exists: see [http://www.kenyabirds.org.uk/goliath.htm] ) and the nightjar ''Caprimulgus longipennis'' whose extravagant mating plumage seems to be an ironic comment on the ungainly wooing of Stephen which immediately follows, down to the leeches and mud-skippers. | ||

| - | Colonel Roche’s description of Waterloo in chapter 1, complete with quotations of two of Wellington’s best-known aphorisms, stands virtually alone in O’Brian’s work as an unmodified slice of historical narrative. | + | Colonel Roche’s description of Waterloo in chapter 1, complete with quotations of two of Wellington’s best-known aphorisms, stands virtually alone in O’Brian’s work as an unmodified slice of historical narrative. |

| + | |||

| + | ==An enigma== | ||

| + | ‘The fleets bound for both the Indies, East and West, had sailed a little early, because of Nostradamus’ (p.43). From a reference on the next page it is clear beyond doubt that the 16th-century French astrologer Michel de Notre-Dame is meant; but what particular passage in his enigmatic prophecies did O’Brian envisage as having a bearing on the date chosen by merchantmen at Funchal to weigh anchor for their annual trading voyages? It is a historical fact that the summer of 1816 was a particularly poor one; is there perhaps a suggestion that Nostradamus had predicted this (or was deemed to have done so), and that the Funchal traders had set out early so as to avoid the unseasonable storms that this prophecy had led them to expect? | ||

| + | |||

Revision as of 17:32, 6 June 2007

Blue at the Mizzen is the twentieth and last completed volume of the Aubrey-Maturin series, written during 1999 in the rooms at Trinity College, Dublin (Stephen Maturin’s alma mater), to which O’Brian retired after the death of his wife.

Page references are to the HarperCollins paperback edition.

Contents |

Plot introduction

For more details about the plot, which will contain spoilers, see Summary for Blue at the Mizzen

Jack Aubrey is in high feather after the successful capture of a Turkish treasure-galley, but there are signs of trouble ahead; his crew disintegrates into riot and desertion at Gibraltar after the distribution of prize-money, a token of the much greater dissolution that must surely follow now that the war is over. First, however, there is the long-delayed mission to Chile, to support the local independence movement under the guise of a hydrographical survey. Surprise first returns to England for refitting and Jack receives a possibly two-edged compliment from a royal personage; then, on the voyage out, she calls at Freetown, where Stephen has a rendezvous of intense personal significance with a most unusual zoologist. Ahead lie a perilous voyage round the Horn and a bewildering course amongst the shifting policies and influences of the Chilean revolutionary factions, still further complicated by an unruly subordinate captain. There is no lack of action, and at the end Jack receives a piece of news for which he has been preparing throughout his seagoing life.

Time Summer 1816-early 1817.

Historical context

Blue at the Mizzen ranks only a little behind The Mauritius Command as a book that is grounded in actual history. Admiral Lord Cochrane, whose career had provided a foundation for Master and Commander and The Reverse of the Medal, returns to cast a double shadow; on the one hand there is an incipient portrait of him under the name of Sir David Lindsay, and on the other the principal incidents of Chapters 9 and 10 – the Valdivia action and the capture of the Esmeralda – are taken from real exploits achieved by Cochrane in 1817. The dissensions among the Chilean leaders are also founded on fact, although O’Brian seems to have brought them forward in time, partly no doubt to provide a plausible reason for Jack’s ultimatum in chapter 10, but also because of the author’s long-standing fascination with the idea of conflicting powers around and behind the throne; in fact Bernardo O’Higgins and San Martín (here represented as O’Higgins’s supplanter) worked together in the early years of Chilean independence, and it was not until 1823 that a reaction by clericalists and landowners undermined O’Higgins and drove him into exile.

==Major characters in Blue at the Mizzen== (h) : historical

- Capt. John Aubrey, RN Post-captain seconded to the Chilean revolutionary junta

- Sophia (Sophie) Aubrey Wife to Capt. Aubrey

- Admiral Lord Barmouth Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet

- Isobel, Lady Barmouth Wife to Admiral Lord Barmouth; a childhood friend of Jack Aubrey

- Miguel Carrera, President of the Chilean Junta (perhaps to be identified with the historical José Miguel Carrera Verdugo, Governor of Chile during the first period of independence (1810-1814)

- John Daniel Master's mate in Surprise

- Austin Dobson Naturalist and member of the Royal Society (named apparently after the poet Austin Dobson (1840-1921), possibly in honour of his patriotic ballad with the refrain ‘Where are the galleons of Spain?’)

- Horatio Hanson First-class volunteer; natural son of HRH the Duke of Clarence

- Lieutenant Harding First lieutenant of Surprise

- Amos Jacob Jewish jewel-merchant and intelligence agent

- Preserved Killick Steward to Capt. Aubrey

- Sir David Lindsay Former naval officer who has taken service with one of the Chilean revolutionary groups

- Captain Lodge Commander of the American frigate Delaware

- Dr Stephen Maturin Physician, naturalist and voluntary intelligence agent

- Bernardo O'Higgins (h) (1778-1842) Chilean revolutionary leader of Irish descent

- Colonel Roche Guest at Lord Barmouth’s table; an eye-witness of Waterloo

- Mr Shepherd and Mr Store Midshipmen in Surprise

- Algernon (or Henry) Wantage Master's mate in Surprise

- Christine Wood, (née Heatherleigh), Naturalist, widow of the Governor of Sierra Leone

Themes and motifs

At first sight Blue at the Mizzen has rather the look of an elegiac coda, free from major turmoils and echoing earlier and more turbulent themes only in softened form; Jack has reached his goal, Stephen seems to have at least a substantial hope of reaching his, and such fighting as occurs is almost bloodless. However, there are clear signs that O’Brian was already thinking of a further book long before this one was completed. Thus chapter 5 (p.131) refers to the jealousy between Jack’s daughters and Brigid which is developed at some length in 21.

Stephen’s courtship of Christine, prefigured in The Commodore, is another strand which was clearly destined for further weaving. Here it reads for a while almost as a duplicate of his courtship of Diana in HMS Surprise; he finds his love in an exotic place, is received with joy, offers himself to her and is gently rejected. However, Christine’s refusal is far less clear-cut than Diana’s. Her subsequent visit to England, which appears to develop into a permanent settlement, seems a little contrived (why should she exchange her unchallenged reign among the awantibos and chanting-goshawks for the dampness and conventionality of Dorsetshire society?) and suggests that her interaction with Sophie and the children of Jack and Stephen would have been an important part of her unwritten history.

Another personal relationship promises more in the way of dramatic tension than it actually achieves. Sir David Lindsay is clearly derived from Lord Cochrane, and his first interview with Jack seems to foreshadow a situation comparable to that of The Mauritius Command, the success of Jack’s operations being imperilled by his flighty and arrogant subordinate. But this interview turns out to be Lindsay’s only appearance on stage; in the next chapter Stephen records that he and Jack have learned to work in harness, and soon afterwards Lindsay is swept away in a duel. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that O’Brian made less of this character than he had initially intended, perhaps because Lindsay’s introduction came too late in the book. In the event a number of exploits which were in reality Cochrane’s are handed over to Jack himself (see Historical context above).

As for larger issues, there is a note of dissolution which runs through the entire book. The collapse of discipline after the prize-distribution, which Jack foresees on page 5 (‘But there you are: that is your seaman . . . What he cannot bear is sudden wealth’), and which is quickly verified when the ship is forced to return to Gibraltar, prefigures the greater disintegration that must follow when the Navy is reduced to a peacetime establishment; and this in turn casts a shadow over Jack’s prospects, for as Stephen explains to Jacob (chapter 5, p.128), Jack stands in much greater peril of being ‘yellowed’ now that the demand for good sea-officers has been so much reduced by the end of the war. The theme of disorder and desertion returns in the final pages (chap. 10, p.251), this time as a result of too little money rather than too much (the Chileans have failed to produce any pay for Jack’s men); in other words the old certainties of active service are dissolved, so that good and evil fortune alike bring with them the threat of disintegration.

The perils of peace (a phrase which might almost have served as a subtitle for the book) are seen from another angle on page 67 (chap.3); an interval of pleasure and tranquillity at Woolcombe is overshadowed by growing problems on and around the estate, for the resumption of imports has affected the demand for home-grown corn, and the humbler farm-workers are suffering as their employers endeavour to cut their losses.

By way of contrast, chapter 5 also gives us the last of O’Brian’s grand descriptive set-pieces in his account of Christine’s environment on the outskirts of Freetown. Like the Buddhist temple in The Thirteen-Gun Salute, it is an idealised scene, an earthly paradise, rather than a wholly realistic portrayal – Sierra Leone was reckoned as one of the unhealthiest places in all Africa, and indeed Stephen nearly takes his death there in The Commodore – but one which is given verisimilitude by a number of precise details of fauna and flora, from the giant heron (Ardea goliath actually exists: see [1] ) and the nightjar Caprimulgus longipennis whose extravagant mating plumage seems to be an ironic comment on the ungainly wooing of Stephen which immediately follows, down to the leeches and mud-skippers.

Colonel Roche’s description of Waterloo in chapter 1, complete with quotations of two of Wellington’s best-known aphorisms, stands virtually alone in O’Brian’s work as an unmodified slice of historical narrative.

An enigma

‘The fleets bound for both the Indies, East and West, had sailed a little early, because of Nostradamus’ (p.43). From a reference on the next page it is clear beyond doubt that the 16th-century French astrologer Michel de Notre-Dame is meant; but what particular passage in his enigmatic prophecies did O’Brian envisage as having a bearing on the date chosen by merchantmen at Funchal to weigh anchor for their annual trading voyages? It is a historical fact that the summer of 1816 was a particularly poor one; is there perhaps a suggestion that Nostradamus had predicted this (or was deemed to have done so), and that the Funchal traders had set out early so as to avoid the unseasonable storms that this prophecy had led them to expect?

| Books in the Aubrey-Maturin Series by Patrick O'Brian | |

|

Master and Commander | Post Captain | HMS Surprise | The Mauritius Command | Desolation Island | The Fortune of War | The Surgeon's Mate | The Ionian Mission | Treason's Harbour | The Far Side of the World | The Reverse of the Medal | The Letter of Marque | The Thirteen-Gun Salute | The Nutmeg of Consolation | Clarissa Oakes/The Truelove | The Wine-Dark Sea | The Commodore | The Yellow Admiral | The Hundred Days | Blue at the Mizzen | 21: The Final Unfinished Voyage of Jack Aubrey | |

| Other books by Patrick O'Brian | |