London

From WikiPOBia

Contents |

Definition from the Era

(The information in this section is from the 1771 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Please do not make edits to this section. Content is presented in its original form as to spelling and grammar use. This is what an educated person of Aubrey and Maturin's time would have known)

The metropolis of Great Britain where the meridian is fixed on British maps, lies on 51° 32' N lat on the river Thames, and the greatest part of the north side of that river. The form of London including Westminster and Southwark, comes pretty near to an oblong square, five miles in length, if measured in a direct line from Hyde-Park to the end of Limehouse, and six miles if we follow the winding of the streets; the greatest breadth is two miles and a half, and the circumference of the whole sixteen of seventeen miles, but it is not easy to measure it exactly on account of its irregular form. The principal streets are generally level, exceedingly well built, and extended to a very great length,; these are inhabited by tradesmen, whose houses and shops make a much better figure than those of any tradesmen in Europe. People of distinction usually reside in elegant squares, of which there are great numbers at the west end of the town near the court. What mostly contributes to the riches and glory of this city, is the port, whither several thousand ships of burden annually resort from all countries, and where the greatest fleets never fail to meet with wealthy merchants ready to take off the richest cargoes. The number of persons in the whole place are computed to be about eight hundred thousand. (C-L pg 1004)

Additional information

In Britain's first national census, taken in the same year (1801) when Jack Aubrey and Stephen Maturin first met, the population of London was given as just under 959,000; it was to pass a million within the next ten years. The overall dimensions given above are still valid in this period, but much open ground had lately been built over; thus St. George's Fields, south of the river, had been a vast open space when Jack was a boy - in 1780 tens of thousands of people had gathered there to begin the anti-Catholic 'Gordon Riots' - but by 1812 they had become a warren of mean streets where Stephen became hopelessly lost on his way to visit Jack in the Marshalsea prison (see The Reverse of the Medal).

The river Thames, flowing from west to east, forms a series of bends roughly in the shape of a broad and shallow capital M. The original Roman settlement lay north of the western half of the M; its ancient walls, fragments of which are still visible, defined the commercial district known as the City - already a centre of worldwide financial dealings (London had gradually replaced Amsterdam as the heart of international finance during the previous century), but also a thriving centre for merchants and craftsmen of all kinds. The Tower of London, home of the Royal Ordnance Board for centuries, marks the eastern end of the City; press-gangs working on the Thames and in the streets of the capital would use Tower Green, on the western side of the Tower, as a rallying-point.

Westminster, the home of Parliament, lies on the left-hand upright of the M. (The old Palace of Westminster, where Jack followed his father in haranguing the Government and embarrassing his powerful friends, was burned down in 1834.) A little to the north was the Admiralty, with its back to the river and its front looking across Whitehall, a fine street named after a 16th-century royal palace on the eastern side; of this only the early 17th century Banqueting House survived and still survives. Black's Club (O'Brian's name for the historical 'White's') was also close to the Park, which, together with the smaller Green Park to the north-west and the much larger Hyde Park northward again, provided a much-needed open space at the fashionable west end. The districts immediately to the east of the triple Parks (Mayfair, St. James's and Soho) had been developed in the first half of the eighteenth century with dignified terraces and squares; a handsome street, quaintly named Piccadilly after a 17th-century fashion accessory, bounded this area on the southern side. Diana Villiers and Sir Joseph Blaine both had their town-houses in this region. From 1811 onward there was another wave of elegant building farther north, instigated by the Prince Regent and featuring the new Park which still bears his name.

Eastward of these recent developments and westward of the City was a quarter largely colonised by lawyers, with the four 'Inns of Court' (which provided education for aspiring 'barristers' [courtroom lawyers] and accommodation once they were 'called to the Bar') as its foci; these were the Inner and Middle Temples near the river and Gray's Inn and Lincoln's Inn farther north.

At the poorer eastern end, beyond the City, the right-hand upright of the M is formed by one side of the peninsula known as the Isle of Dogs; the river flows round this in a U-bend. From 1800 onwards, major new commercial docks were under construction on the Isle of Dogs itself and at Wapping to the west and Blackwall to the east. Deptford, the oldest of the royal dockyards, was at the base of the U on the southern bank, and just eastward was Greenwich, where King Charles II had founded an observatory in the 1660s. Also at Greenwich was the Hospital for retired seamen (1694).

The river itself, severely polluted and a constant source of disease for rich and poor alike (there were no scientific sewage facilities until the 1850s), was nonetheless a major transport route both to and through the capital. The 13th-century London Bridge, which linked the ancient City to Southwark on the south bank, set the upstream limit for ships and boats of any size, so that the dockland area was confined to the Pool of London, east of the bridge, and to the newer shipyards and wharves further downstream; but small rowing-boats known as wherries functioned as taxicabs all along the river, served by numerous stairs and jetties on both banks. (On land, public transport consisted largely of 'hackney-carriages', mostly gentleman's coaches which had come down in the world; the omnibus and the Victorian 'cab' had not yet arrived.) By 1800 new bridges had been built at Westminster and at Blackfriars in between; three more would be added over the next twenty years.

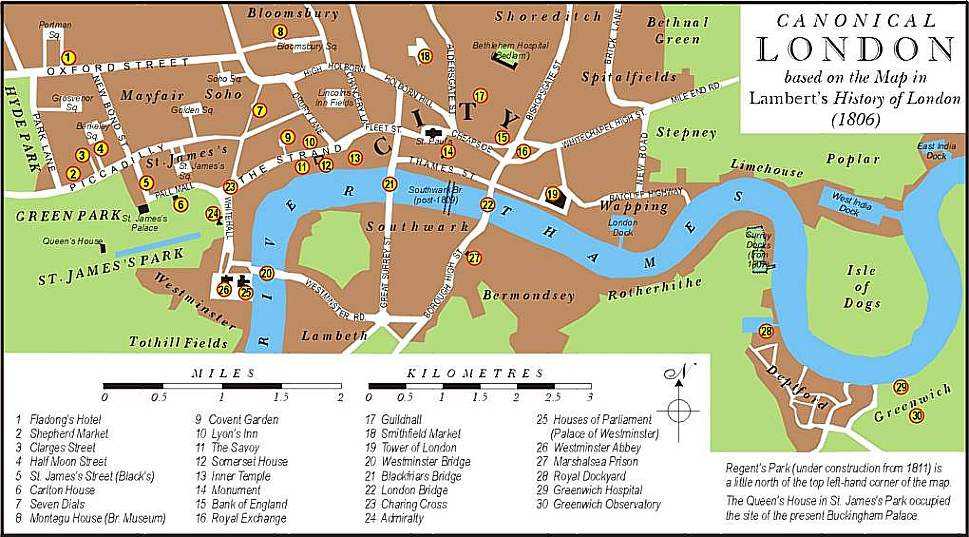

== Map of London, circa 1810 ==  This greatly simplified plan is perhaps best used in conjunction with the much larger-scale map available online (see External links below). An extended key to the 30 canonic sites shown on our own map is in preparation.

This greatly simplified plan is perhaps best used in conjunction with the much larger-scale map available online (see External links below). An extended key to the 30 canonic sites shown on our own map is in preparation.

Key to the map

| SPOILER WARNING: Plot or ending details for "series" follow. |

- 1 Fladong's Hotel, on the corner of Oxford Street and Orchard Street, was a popular haven for naval officers.

- 2 Shepherd Market - not an individual street or square but a small residential estate lying north of the western end of Piccadilly. Sir Joseph Blaine's private house was here.

- 3 Clarges Street, where Stephen sought Diana in vain (Desolation Island).

- 4 Half Moon Street, where Diana maintained a town house after her marriage.

- 5 St. James's Street, location of Black's and, opposite, Button's which Andrew Wray frequented.

- 6 Carlton House, residence of the Prince Regent.

- 7 Seven Dials, a meeting-place of seven roads, formed the southern part of the very poor and squalid district of St Giles. Barret Bonden lived here as a boy.

- 8 Montagu House in Great Russell Street was the location of the original British Museum (founded 1753). The present building dates from 1828.

- 9 Covent Garden, laid out as an Italianate piazza in the 1630s. At the theatre here (not yet exclusively an opera-house), Stephen attended Cimarosa's Le Astuzie Femminili and grieved over Diana's loss of integrity (Post Captain).

- 10 Lyon's Inn, where 'Ellis Palmer' (Paul Ogle) had his lodgings (The Reverse of the Medal).

- 11 The Savoy, site of The Grapes where Stephen kept a permanent room.

- 12 Somerset House, home of the Navy Board and of the Royal Society.

- 13 The Inner Temple, one of the four Inns of Court.

- 14 The Monument, a column commemorating the great fire of 1666, where Jack Byron goes aloft with two live turkeys under his arm (The Unknown Shore).

- 15 The Bank of England, founded 1696. Sir John Soane's fine building, under construction in 1815, was destroyed in the 1920s.

- 16 The Royal Exchange (burned down 1838) was largely a centre for luxury shops. Jack Aubrey stood in the pillory in front of it (The Reverse of the Medal).

- 17 The Guildhall (15th century), headquarters of the City of London authorities. Jack was put on trial here (The Reverse of the Medal). It still stands, albeit much restored.

- 18 Smithfield Market, London's centre for meat trading. Livestock was driven here through the streets. The Navy Board bought much of its beef and pork here.

- 19 The Tower of London, built in the late 11th century and little changed since 1500; headquarters of the Board of Ordnance.

- 20-22 Westminster (1750), Blackfriars (1769) and London (13th century) Bridges. London Bridge had been cleared of the houses and shops which once lined it, but its nineteen stone arches remained as a hazard to river traffic until it was dismantled in 1830.

- 23 Charing Cross, often regarded as the central point of London.

- 24 The Admiralty building (1760s) still stands.

- 25 The Palace of Westminster (the correct name for the Houses of Parliament). Only the 12th-century Westminster Hall survives from the buildings that Jack would have known.

- 26 Westminster Abbey (12th-17th century).

- 27 The Marshalsea Prison, chiefly used for debtors. Jack was confined here before his trial.

- 28 Deptford Dockyard, the oldest of the royal yards.

- 29 Greenwich Hospital, designed by Sir Christopher Wren, a refuge for aged seamen.

- 30 Greenwich Observatory, from which longitudes are measured.

In the Canon

External links

Justin Reay's 'Lissun London Locator' gives detailed descriptions of canonical landmarks as they were and as they are now, a table of London sites mentioned in each book, and links to large-scale images of Christopher Greenwood's map of 1827.