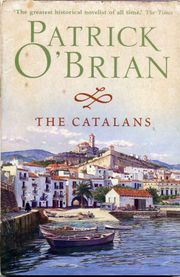

The Catalans A Novel

From WikiPOBia

The Catalans is Patrick O'Brian's second adult novel, written at Collioure and published in 1953. The original British-market title was The Frozen Flame, but the most recent British edition (HarperCollins paperback, 2006) has adopted the more straightforward American title.

Contents[hide] |

Plot introduction

For more details about the plot, which will contain spoilers, see Summary for The Catalans A Novel

Alain Roig, a doctor working in the Far East, is summoned back to his childhood home on the French-Catalonian border to resolve a bitter family dispute: his cousin Xavier, a widower and a respected lawyer and local politician, has horrified his female relatives by planning to marry his secretary Madeleine, the beautiful daughter of a local shopkeeper. Alain conscientiously probes the motives and intentions of the ill-matched pair. Xavier is revealed as a man who believes, with horror, that he has lost the ability to feel; his wife is long dead, he has found it impossible to love his graceless son Dédé, and Madeleine represents his last hope of a connection with the world of life and emotion. Alain's own detachment is undermined as he re-establishes himself in the once familiar world of fishing-fleet and vintage, whose ancient habits and rituals provide both a background and a catalyst for the dramatic resolution.

Major characters in The Catalans A Novel

- Alain Roig An idealistic physician

- Margot Roig Alain's aunt, matriarch of the family

- Xavier Roig Alain's cousin, lawyer and mayor of Saint-Féliu

- Madeleine Fajal Xavier's typist and intended bride

- Francisco Cortade Fisherman and artist, Madeleine's estranged husband

- Marcel Dumesnil Failed novelist; friend of Francisco

Themes and motifs

This book began as a study of a man without a heart: a decent, civilised, humane person who has to live with the sense that he has no soul. However, Xavier is not the central character for much of the time, and in a larger sense The Catalans is a novel about pretence: not the raw self-seeking hypocrisy so familiar from Dickens or Thackeray, but a kind of dogged, weary, even despairing falsification of one’s inner life – disguising it where it exists, fabricating an imitation out of spurious ingredients where it does not – undertaken not with any hope of gain but simply for the sake of expediency or for a quiet life or even out of a mistaken sense of duty. All the main characters are affected by this flaw in their own respective ways. The two artists, Francisco the painter and Marcel the writer, show it in its simplest form: the one posing as an unspoiled folk-artist, the other a burned-out case who struggles to uphold his reputation among his relatives by binding up copies of foreign novels with forged title-pages and presenting them as translations of his own works. Alain, for his part, is constrained by the attitudes of those around him to mimic the altruistic and sympathetic manner that they expect from a doctor. Aunt Margot feels herself bound to move against Madeleine, whom she genuinely likes and has hitherto encouraged, because of her belief that Xavier’s liaison will not only create scandal but also destroy his political credibility. And Xavier himself, appalled by the consciousness that he met his wife’s illness with irritation and her death with relief, and that he has never felt anything except disgust for his son, can find no other response than to act out the part of an upright, responsible, charitable citizen; he is certain that these pretences cannot save him from eternal damnation, and yet he cannot let go of them.

Madeleine herself is not immune; she finds Xavier physically repulsive, but her sense of obligation, born of his real kindness and courtesy towards her, almost results in her binding herself in a marriage which must be joyless and desolate at best. And yet, in an ironic way, Xavier is right in thinking that she may point the way into a better and happier world. She has been brought up with tenderness and affection, and this has set its mark on her: as a child ‘she was dirty . . . untruthful and dishonest. But being less battered, she was less dirty, untruthful and dishonest than the rest.’ In short, without being in any way a saint, she is set apart from the petty concerns and obsessions of the people about her; she has a kind of rightness which is beyond analysis – a concept which O’Brian will explore again with the character of Diana Villiers.

The authorial position

In this book, O’Brian for the first time achieves the distinctively detached and impersonal narrative voice of his mature work. There is a peculiarity about this which may easily escape notice: it has the remoteness and impassivity of a deity, but not the omniscience. Instead of knowing and seeing everything, this narrator chooses to co-opt the senses and the mind of one character at a time, seeing and hearing with that person’s eyes and ears and thinking that person’s thoughts; all the other personages of the story are seen only from the outside, as the chosen character may be presumed to perceive them or as any observer present at the scene might have perceived them. In the Aubrey-Maturin novels, this treatment is almost always bestowed on Stephen Maturin, occasionally on Jack Aubrey, but very rarely on anybody else. (The model for this approach seems to be Jane Austen; in Mansfield Park, for example, she uses Fanny as a medium for the most part, just as O’Brian uses Maturin.) In The Catalans the focus is generally on Alain, although Madeleine has a chapter (the second) largely to herself, while in the final pages the spotlight shifts to Xavier with startling effect – a technique perhaps derived from some of Kipling's later stories, such as 'Aunt Ellen' – turning what might easily have been an over-tidy romantic ending into something both poignant and disturbing.

Echoes from the author's life

During his long soliloquy in chapter IV, Xavier describes his struggles to educate his deeply unsatisfactory son. The monstrous Dédé ('[H]e felt more malice than I should ever have supposed a child could contain') is clearly a pure invention, but when Xavier accuses him of being affectedly 'quaint' and giving 'a performance of himself as an arch, winning little boy', he closely echoes occasional complaints made in O'Brian's Welsh diaries, as quoted by his stepson and biographer Nikolai Tolstoy, concerning his own son. Equally true to life is the passage where Xavier, son of a bullying father, reveals his deep shame at having in turn become a domestic tyrant.

Less distressingly, the novel makes extensive use of the scenery and society of the Franco-Catalan border where O'Brian had settled in 1949. In Alain's struggles to carry the basket of grapes down the hillside (chap. VIII), O'Brian reproduces his own enthusiastic if not entirely competent efforts to share in the work of his new neighbours, just as he had done in the sheep-shearing episode in Testimonies.

Footnotes

The place-name Prabang, used for the territory (apparently somewhere in present-day Malaysia) where Alain has been stationed, will reappear in The Thirteen-Gun Salute.

Alain foreshadows Stephen . . .

In chapter 3 (page 64, HarperCollins paperback), Alain reacts to the sight of a pretty girl (not Madeleine) with a strikingly Irish idiom:

'My God,' he said, internally. 'Here's freshness; here's bloom. Here's the lovely sin of the world.'

It seems that already, fifteen years before Master and Commander, O'Brian had perceived something oddly compatible between Erin and Catalunya - a union which was to give birth to the character of Stephen Maturin.

. . . and Jack

From the same chapter (ibid., p.70)

At this moment the phoenix (a suspicion that he might be able to make an epigram about cuckoos, phoenixes, and fornication drifted across the surface of Alain's mind) was bent over a heap of papers among the ruins of their dessert.

In much the same way, Jack Aubrey often trembles on the edge of a pun or witticism which he cannot quite formulate to his satisfaction.